[At the time of its detection in California, goldspotted oak borer was described as Agrilus coxalis. It has since been reclassified as Agrilus auroguttatus. The name A. coxalis has been assigned to a similar beetle found in southern Mexico and Guatemala (Coleman et al. 2012). Several oak species in California are under threat from other non-native invasive pests, including polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers; Mediterranean oak borer; and sudden oak death pathogen.]

Genetic studies have demonstrated that the GSOB (Agrilus auroguttatus) is native to southeastern Arizona (Coleman et al. 2012). It was probably introduced to California in the 1990s via infested firewood. Coleman and Seybold (2009) explain why it is unlikely that the beetle expanded its range westward into California through natural dispersal across hundreds of miles of desert terrain which does not support oaks.

Since its introduction to eastern San Diego County (see below), the GSOB infestation has burgeoned into a regional epidemic. It is the primary agent of oak mortality across southern California, an area that makes up roughly 37 million square miles. GSOB infestations now occur across a region encompassing six counties (San Diego, Riverside, Orange, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, and Ventura) and five mountain ranges (San Jacinto, Santa Ana, San Bernardino, and San Gabriel, and Santa Susana Mountains).

Infestations are now found in and near inholdings in three National forests –the Cleveland, Angeles and San Bernardino NFs. The Forests are actively managing infested areas, monitoring the situation annually, and participating in community outreach and collaboration (B. Kyre, pers. comm.).

Several State and County parks have been affected, including Mount San Jacinto, Cuyamaca Rancho, Silverado Canyon, and Palomar Mountain State parks; and Dos Picos, Ramona Preserves, Luis A. Stelzer, Marion Bear Memorial, William Heise, East and Rice Canyons, Newhall and Whitney Canyon, Santa Clarita, and Box Canyon county parks. (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

Several Native American reservations in the region have also been invaded. These include the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians in San Diego County, the Pala Band of Mission Indians, the Mesa Grande Reservation, Santa Ysabel Reservation, and Los Coyotes Reservation (Joelene Tamm, pers. comm.).

Years of slow expansion have been punctuated by periods of explosive growth. For example, annual mortality in 2017 is estimated to have reached 40,000 trees (USDA Forest Service, 2017). While there has been a decline in the rate of new mortality in the 2020’s, thousands of trees continue to die each year, bringing the officially documented cumulative total to over 142,000 (Joelene Tamm, pers. comm. September 2025).

As Joelene Tamm explains, however, estimates derived from the Forest Service’s Aerial Detection Surveys (ADS) significantly underestimate the total number of trees killed. The ADS program is designed to observe broad trends. Its methodology is less effective at capturing mortality within fragmented urban landscapes or narrow riparian corridors, especially for oaks because of their sprawling codominant canopies. Ground-based reports reveal a much higher density of damage than can be accurately assessed from the air. She cites examples from Palomar Mountain, William Heise County Park, and the reservation of her own La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians. Tamm concludes that when accounting for the high-density mortality pockets that are difficult to quantify from the air and the thousands of uncounted dead trees along roads and near homes and in open woodlands, the true number of oaks lost to the Goldspotted Oak Borer probably approaches 200,000 (J. Tamm, pers. comm. September 2025).

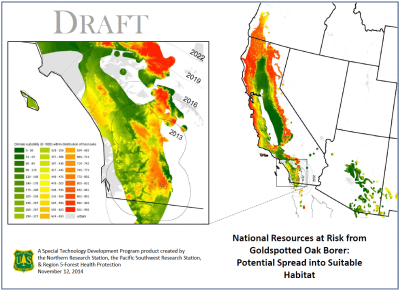

There is a strong potential for GSOB to infest oaks in much of California. A risk assessment conducted by Coleman and Seybold (2009) defined areas at highest risk of GSOB establishment stretch along the Coastal Mountain Range and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range north the length of California and into southwest Oregon. The frequency with which GSOB has been transported to new locations by the movement of firewood demonstrates that risk of spread to these areas is very real. At least 20 noncontiguous satellite infestations have been detected in southern California (J. Tamm, pers. comm.).

GSOB kills three species of oaks native to southern California: coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), California black oak (Q. kelloggii), and canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis). The beetles prefer the largest trees; one source says branches larger than 12 inches (Coleman and Seybold, 2009); a second source says trees with DBH greater than 18 – 20 inches [~45 cm]). The California oak communities have not evolved defenses. There are a few natural enemies of the GSOB in California such as woodpeckers and some parasitoids including Balcha indica, but they are neither individually nor collectively successful at keeping GSOB populations in check [see more info here].

Death of these trees causes numerous ecological impacts. Oaks provide food, habitat, and climate control for hundreds of species. Dead oaks are potential hazards, especially where they might fall on dwellings, roadways, and recreational areas. Oak mortality also changes the fuel load structure and composition across the landscape, which can increase the probability and severity of wildfire (USFS PSW S&P R5-RP-022 Oct 28, 2008). Urban trees provide important ecological services, including shade which reduces energy use and expense associated with air conditioning; they also reduce storm water runoff (Zeleznik, 2008). Larger trees – such as oaks – provide more of these services (Love et al. 2023).

Spread of the GSOB Infestation

In all cases, the pathway of movement is believed to be via infested firewood since these oaks are not harvested for timber, and nursery stock is too small to support GSOB larvae (Coleman and Seybold, 2016). The result is establishment of numerous disjunct populations that drove new expansions of GSOB, contributing to its rapid spread throughout the region.

Oak decline was observed by 2002 in eastern San Diego, specifically in the Cleveland National Forest and Cuyamaca Rancho State Park (USFS PSW S&P R5-RP-022 Oct 28, 2008). However, the causal agent was identified only in 2008 (Coleman et al. 2012). Interestingly, the first GSOB adult was trapped in 2004 in San Diego County. In the subsequent 20 years, numerous foci of infestation merged (K. Corella, pers. comm.).

The second county to detect a GSOB outbreak was Riverside County. A disjunct population was discovered in 2012 in the towns of Idyllwild and Pine Cove in the San Jacinto Mountains. These towns are surrounded by a second National Forest, San Bernardino; it is home for many black and canyon live oak (Scott and Turner, 2014). Despite control efforts (e.g., removal of infested trees), this infestation continues to intensify. By the 2020’s, the regional infestation rate averaged 20% higher in areas of human activity and infrastructure (K. Fryer, Mountain Communities Fire Safe Council, pers. comm., August 2024).

Two years later, a third county became involved with the 2014 discovery of another disjunct population in Weir Canyon, in northern Orange County. By 2024, almost 20 separate infestations had been detected in Orange County (J.D. Clark pers. comm., based on CalInvasive GSOB map).

Los Angeles County followed a year later, in 2015. Yet another disjunct population was found in Green Valley, a canyon dominated by one of the most vulnerable hosts, coast live oak. While GSOB was detected on private properties, the settlement is surrounded by a third National Forest, Angeles National Forest. Despite active management (see below), a new disjunct infestation was found in 2024 in the Santa Clarita valley. GSOB had been there for at least 5 years (K. Corella, CalFire, pers. comm., June 2024). The Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning is drafting two plans focused on oak management. A Countywide Community Wildfire Protection Plan which will address non-native tree pests. The County Forest Management Plan is the second (J.D. Clark pers comm.).

GSOB was detected in a fifth county – San Bernardino – in 2018. The initial detection at Oak Glen was followed shortly afterwards by additional infestations farther north, in the communities of Forest Falls, Sugarloaf, Big Bear, and Yucaipa. Other infestations were detected to the West, in Wrightwood. Here the host is California black oak (Q. kelloggii). Again, the detection was tardy; this outbreak was likely established by 2013.

In San Bernardino County, CalFire continuously surveys for GSOB within the Big Bear and Sugarloaf communities. USDA Forest Service monitors surrounding oak habitat. The Inland Empire Resource Conservation District (IERCD) also surveys around other communities (B. Kyre, USDA Forest Service, pers. comm.), including the private properties of willing owners in Wrightwood. A National Forest Foundation grant is supporting treatments for removal of amplifier trees (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

Observing the beetle’s spread, officials in the sixth county, Ventura County, began trapping at targeting green waste facilities and campgrounds in 2023. In the summer of 2024, GSOB was detected on private property in Box Canyon in the Santa Susana Mountains. A second, much larger, infestation (~150 acres) has since been detected at higher elevations on land owned by Ventura County Recreation and Parks and the Mountain Conservation Authority. Approximately one-third of Ventura County is highly vulnerable due to its large population of old growth oaks (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

The region’s urban forests of the affected region are also under threat. The California Urban Forest (CUF) Inventory documents nearly 2.5 million trees in urban areas in the South California Coast region (Love et al. 2022). The oak genus (Quercus) is the second most-abundant native genus in the state’s urban forest, making up 6.5% of the trees. As noted above, GSOB preferentially attacks large trees. While most of the large trees in the urban forest statewide are not oaks (Love et al. 2022), at least 30,000 of the 152,594 urban coast live oaks in 287 cities statewide (Pawlak et al. 2023) have diameters greater than 45 cm (Love et al. 2022). The highest presence of oaks in urban forests in the South is in Santa Barbara – which has not yet been invaded by GSOB (Pawlak et al. 2023).

According to Dr. Thomas Scott of the University of California Riverside, built-up sections of Los Angeles have between 250,000 and 300,000 coast live oak trees. Some 92,000 acres of single-family homes are shaded by such oaks. All are vulnerable to this pest. Since removing hazard trees can cost as much as $10,000, these homeowners will be severely affected (B. Nobua Behrmann pers. com.).

Response

The goldspotted oak borer is ranked as a level “B” pest by the California Department of Food and Agriculture. This means that most control efforts have been left to other entities. One encouraging result has been growth of an unprecedented amount of collaboration across the affected region of southern California: the USDA Forest Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, CalFire, California Department of Conservation, State parks, agencies of four counties, community Fire Safe councils, regional conservation agencies, several Resource Conservation districts, various Tribes and Tribal Nations, and the University of California extension are working together to accomplish cross-boundary support for GSOB monitoring and management on over 37,000 square miles. Activities include detection and monitoring, treatment off vulnerable trees, removal of “amplifier” trees to slow the infestation’s spread or hazard trees to protect lives and property, and outreach and education. Often the motivation is the link of large expanses of dead trees and increased danger of fire.

In Riverside County, grants from the National Forest Foundation have empowered the local Fire Safe Council to inspect oaks on public and private properties. While at-risk trees were originally sprayed, funding shortfalls have ended that aspect of the program. Officials believe that education and outreach have greatly elevated public awareness and cooperation (K. Fryer, Mountain Communities Fire Safe Council, pers. comm., August 2024). A multi-agency support team with representation from CalFire (lead), USFS, State Parks, County Parks, Fire Safe Council, and County Fire meets quarterly to coordinate the efforts (B. Kyre, pers. comm.).

Los Angeles County authorities began active management in Green Valley after the 2015 detection. Nearly 10,000 “amplifier” trees had been removed as of 2024 (Perez, 2024). The Los Angeles County Agricultural Commissioner/Weights & Measures, the Santa Monica Mountain Resource Conservation District (RCD), and UC Cooperative Extension established a joint “Bad Beetle Watch” program with Ventura County. The project is training agency personnel, tree professionals, and recreationists to detect GSOB. After years of surveys focused on the Santa Monica Mountains, the LA County Fire / Forestry Division is now ramping up surveys in the west end of the oak-dense San Fernando Valley – Santa Susana Mountains since GSOB was found in adjacent Ventura County near the borders between the two counties (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

The Santa Monica Mountains are home to 151,000 oaks (R. Dagit – RCD of the Santa Monica Mountains, pers. comm.). Two GSOB infestations are nearby, in Newhall and Santa Clarita (J.D. Clark pers. comm.). Management of the Newhall and Santa Clarita outbreaks is undertaken by the state agency Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is also exploring the possibility of declaring a local or state emergency related to the risk of the spread of GSOB in the County and to the Santa Monica Mountains [K. Corella, CalFire; pers. comm., June 2024].

In Orange County, a coalition of academics from the University of California and scientists with CalFire and USDA Forest Service are testing various pesticide application approaches (e.g., trunk sprays or systemic trunk injections) and formulations (e.g., emamectin benzoate, Azadirachtin, Bifenthrin, Carbaryl and Dinotefuran). They are also removing heavily infested trees. Orange County Parks is actively surveying and managing the GSOB infestation at a regional park by removing amplifier trees and treating infested trees. Some felled trees, in inaccessible locations, are left in place and treated for a minimum two consecutive years with a trunk spray.

In Ventura County, several agencies — CalFire, Ventura County Fire, Ventura County Resource Conservation District, California Coastal Conservancy, Rivers and Mountains Conservancy, Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, Ojai Valley Land Conservancy, Ventura Fire Safe Council, Ojai Valley Fire Safe Council as well as the state lands commission and Los Padres National Forest – are gearing up educational programs aimed at preventing spread of GSOB to additional areas. The non-governmental organization Tree People helped to spark this effort by elevating the need for a regional GSOB coalition. Efforts are under way to fund and formalize the coalition, with collaboration from California Department of Conservation, CAL FIRE UC Agriculture and Natural Resources (J.D. Clark, pers. comm. August 2025; K. Corella, pers. comm. August 2025).

Despite the damage to state parks, the California State Park agency encourages – but does not require – campers and picnickers to purchase certified clean firewood on site from camp hosts (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

Among Native American reservations in the region, the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians has already removed almost one thousand large coast live oak trees in the Tribe’s campground; another thousand trees must be removed over the next several years. Since 2019, the Tribe has been applying contact insecticides annually on 200 to 300 trees. Obtaining funds to develop the capacity to mitigate the ongoing GSOB invasion has been a constant challenge. In addition, the Tribe has been planting seedlings and conducting research in partnership with UC Riverside, San Diego State University, and UC Irvine. One experiment tests whether low-intensity fire can be used to kill pupae, larvae, and unenclosed adults (which are in outer bark) (J. Tamm, pers. comm.).

A second tribe, the Pala Band of Mission Indians, began a systematic survey of its lands in 2022. At that time, they found light infestation in coast live oak and some dispersal. Hundreds of dead trees are visible from highways bordering the Mesa Grande, Santa Ysabel, and Los Coyotes reservations. Even those reservations that have no oaks on their territories are affected because they harvest acorns as a culturally important food (J. Tamm, pers. comm.).

Two private reserves in Orange County responded aggressively. At Weir Canyon, The Irvine Ranch Conservancy started active management immediately after detection of GSOB in 2014. Actions included annual surveys, treating lightly infested trees, and removing heavily infested or “amplifier” trees. This effort has paid off. By 2019, ~75% of the previously infested trees had no new exit holes. Furthermore, all 173 uninfested trees surveyed remained free of GSOB. Conditions continued to improve. By 2023, only 21 of 187 coast live oaks surveyed had new exit holes – and in most cases only one or two. Weir Canyon is considered a successful control program.

Managers of the California Audubon Starr Ranch Sanctuary began monitoring for GSOB by 2016. No GSOB were detected until 2023 when 64 out of ~300 trees surveyed were infested. Difficult terrain impedes survey and response. Orange County Fire Authority hired contractors to remove amplifier trees and treat others. Monitoring continues (J.D. Clark pers. comm.). These actions are based on recommendations from UC Cooperative Extension (B. Nobua Behrmann pers. comm.).

In Los Angeles County, the Chief Sustainability Officer initiated action targeting GSOB in March 2024, as mandated by in the county’s Early Detection Rapid Response Plan. This action has helped coordinate agencies and consultants. Los Angeles County Regional Planning will target oak-dense communities this year to advocate for oak woodland health, care, GSOB, and importance of not moving or sharing firewood (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

Efforts by Federal Agencies

Two ranger districts of Cleveland National Forest, Palomar and Trabuco, have been applying contact insecticides to high-visit recreation sites for up to six years. Despite these efforts, two new infested locations were found in Trabuco Canyon in 2022 near previously known infestations.

The Angeles, Cleveland, and San Bernardino National forests all have extensive and evolving monitoring and management plans for GSOB. Management includes annual surveying, tree removal and or treatment, firewood sourcing and provision by concessionaires, and restricted wood harvest permits. Each forest has also partnered with various counties, NGOs, FireSafe councils, and Resource Conservation districts to expand outreach, monitoring, and management. Many of the efforts are centered around communities within and adjacent to National Forest boundaries and recreation sites, since they are the main points of GSOB ingress. The fourth National Forest in southern California, Los Padres NF – which lies partially in Ventura and Los Angeles counties – has not yet found any GSOB but is preparing. The Forest conducted a forest health training with heavy emphasis on GSOB in spring 2024 and is in the process of creating its own monitoring and management plan to include preemptive evaluation of environmental concerns under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) and planning.

GSOB management is an important facet of the NF Wildfire Crisis Strategy which encompasses all four National Forests in southern California. Hurdles to management on National Forest land (and all wildland areas) are steep and inaccessible terrain, wilderness designations, designation of sensitive habitat/areas for wildlife, ecological, or heritage sites, and the sheer amount of land managed. Despite this, the forests continue to expand their efforts each year to address the growing GSOB presence (B. Kyre, USDA Forest Service, pers. comm.).

In the early 2010s, scientists looked for possible biocontrol agents in the species’ native habitat in Arizona. Two parasitic wasps that attack GSOB larvae – Calosota elongata and Atanycolus simplex – were identified. They were determined to be present in California, although parasitism rates are much lower for C. elongata in California than in Arizona (Coleman et al. 2012).

Several National parks located in California contain important oak forests and woodlands that are at risk to invasion by GSOB, especially given the importance of firewood in spreading the pest. Yosemite and Kings Canyon National parks and other campgrounds in the Sierra Nevada receive large numbers of campers from the Los Angeles area (Koch, 2012). Both parks contain significant populations of one of the preferred hosts, California black oaks (Q. kelloggii).

In 2014 the National Park Service published a resource guide for firewood management (DiSalvo, 2014). The documents summarized federal plant pest regulations (which have since changed i.e., emerald ash borer is no longer federally regulated domestically) and defined levels of treatment. The guidance advised Park staff to define their park’s forest resources, keep abreast of present and potential forest pest species, and act to manage risks from potentially infested firewood.

The NPS has nation-wide guidance for firewood provided by concessionaires (WASO Commercial Services – Contract Management) that applies to both Yosemite and Kings Canyon-Sequoia. Park concessioners are required to purchase and sell only locally grown and harvested firewood in accordance with state quarantines. However, California does not have relevant quarantines for either firewood as a commodity or for oak pests specifically. The two parks’ websites ask people not to bring firewood obtained from a source more than 50 miles from the parks.

The “Don’t Move Firewood” program keeps track of all relevant quarantines including those in California, a summary can be accessed here. Additionally, the Firewood Scout program (Firewoodscout.org) advises campers on local sources from which to purchase their wood, and California is a participating state. Statewide, a consortium of several agencies, academia, and non-government agencies operate a “Buy It Where You Burn It” campaign that promotes this message with the public and firewood vendors (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

Cooperation Would Be Improved by Coordination

The many entities carrying out monitoring and treatment efforts are not coordinated by any official body. An informal group that meets by conference call every two weeks seeks to disseminate information and advice. A coordinator is urgently needed to enhance the cooperators’ ability to contain GSOB, which has been spreading rapidly (K. Corella pers. comm.).

Funding is a perpetual problem. No agency, not even CAL FIRE, is funded to remove amplifier trees throughout the region. The agency does use its crews to remove GSOB infested trees when they are available, but there is not a designated crew for removing GSOB amplifier trees. Most funding for treating infested trees comes from competitive grants awarded by CAL FIRE or National Forest Foundation.

The California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection (which is appointed by the Governor) has officially designated a Zone of Infestation (ZOI) for GSOB. It first acted in September 12, 2012. The Zone was expanded in 2014, 2016, unties and 2020 as the infestation spread. The 2020 map [PDF] covers all known areas with susceptible oaks in the affected counties so as to minimize need to update the map each time a new infestation was detected (K. Corella, pers. comm.). The Zone of Infestation formally recognizes GSOB as a threat to California’s forest and woodland resources and sought to raise awareness among the governor, legislature, and public. The action was also intended to foster collaborative efforts to manage the beetle.

Joelene Tamm, Vice Chair of the California Forest Pest Council Southern California Committee (CFPC), is leading an initiative to address wildfire risks from invasive pests like GSOB, South American Palm Weevil, and Invasive Shothole Borers. She has presented a pest update with potential solutions to the California Board of Forestry (BOF) and followed up with a presentation to the BOF Resource Protection Committee, which is now identifying responsive actions. The Governor’s Wildfire Task Force is considering incorporating the topic into future meetings. The initiative’s core message is that the state must address the root cause of pest proliferation, as treating the symptom of wildfire alone is an unsustainable strategy (Tamm, pers. comm. August 2025).

Project CAPTURE

USFS scientists and managers developed a conservation priority-setting framework for forest tree species at risk from pest and pathogens as well as other threats. The Project CAPTURE (Conservation Assessment and Prioritization of Forest Trees Under Risk of Extirpation) uses FIA data and expert opinion to group tree species under threat by non-native pests into vulnerability classes and specify appropriate management and conservation strategies. The scientists prioritized 419 tree species native to the North American continent. The analysis identified 15 taxonomic groups requiring the most immediate conservation intervention because of the tree species’ exposure to an extrinsic threat, their sensitivity to the threat, and their ability to adapt to it. Each of these 15 most vulnerable species, and several additional species, should be the focus of both a comprehensive gene conservation program and a genetic resistance screening and development effort. GSOB is not known to be a threat to any of these 15 most vulnerable species.

In its native range of southern Arizona, GSOB is a secondary pest on Emory oak (Quercus emoryi) and silver-leaf oak (Q. hypoleucoides). Oak mortality from GSOB in this area is negligible except during droughts (Coleman and Seybold, 2011; Gil et al. 2024).

To slow the spread of GSOB to vulnerable oaks farther North, an informal consortium has been formed (https://ucanr.edu/sites/gsobinfo/) which aims at informing citizens. Part of the message urges people not to transport oak firewood or logs and to remove dead or recently dying oaks with heavy infestations to limit localized growth of the beetle population. The bark from felled oaks should be chipped into three-inch pieces or smaller and left on-site; the beetles will not survive in wood chips of this size. Other management efforts include an expanded survey program in California, search for potential attractants for GSOB to increase survey efficacy, and investigation of the area-wide impact of the beetle and the effect of drought on the success of GSOB in southern California (J.D. Clark pers. comm.).

For more information on this pest, please visit:

- UC Cooperative Extension Goldspotted Oak Borer information a.k.a GSOB.org

- UC Riverside, Center for Invasive Species GSOB Species Profile

- UC Integrated Pest Management guidelines for GSOB

Sources

Coleman, T.W., V. Lopez, P. Rugman-Jones, R. Stouthamer, S. J. Seybold, R. Reardon, and M.S. Hoddle. 2012. Can the destruction of California’s oak woodlands be prevented? Potential for biological control of the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus auroguttatus. BioControl, 57: 211–225 DOI 10.1007/s10526-011-9404-4

Coleman, T.W. and S.J. Seybold. 2008. Previously unrecorded damage to oak, Quercus, in southern California by the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). Pan-Pacific Entomologist, 84: 288-300

Coleman, T.W. and S.J. Seybold. 2009. Tree Mortality from the Goldspotted Oak Borer in Oak Woodlands of Southern California. In Frankel et al. Fourth Sudden Oak Death Science Symposium June 09 Meeting Abstracts

Coleman, T. and S.J. Seybold. 2016. Goldspotted Oak Borer in Calif: Invasion History, Biology, Impact, Management, & Implications for Mediterranean Forests Worldwide. Chapter 22 in T.D. Paine and F. Lieutier, Editors Insects and Diseases of Mediterranean Forest Systems. Prairie Lights.

DiSalvo, C.L.J. 2014. Reducing ecological risks associated with pests in firewood: Guidance for park managers. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRMD/NRR—2014/817. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Gil, A.S., Rogstad, K.A., Nickerman, J., Tischler, C. Hall, Z. et al. 2024. Forest Health Conditions in Arizona and New Mexico – 2023 https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd1196054.pdf

Koch, F.H., D. Yemshanov, R.D. Magarey, and W.D. Smith. 2012. Dispersal of Invasive Forest Insects via Recreational Firewood: A Quantitative Analysis J. Econ. Entomol. 105(2): 438-450 (2012). Online at https://admin.forestthreats.org/products/publications/Dispersal_of_invasive_forest_insects.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2013.

Love, N.L.R., V. Nguyen, C. Pawlak, A. Pineda, J.L. Reimer, J.M. Yost, G.A. Fricker, J. D. Ventura, J.M. Doremus, T. Crow, and M.K. Ritter. 2022. Diversity and structure in California’s urban forest: What over six million data points tell us about one of the world’s largest urban forests. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 74

Pawlak, C.C., N.L.R. Love, J.M. Yost, G.A. Fricker, J.M. Doremus, M.K. Ritter. 2023. California’s native trees & their use in the urban forest. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 89 (2023)

Perez, N. 2024. Invasive Beetle Kills at Least 90,000 Trees: Can Indigenous Cultural Burns Help? LAist https://laist.com/news/climate-environment/an-invasive-beetle-has-killed-at-least-90-000-socal-trees-can-indigenous-cultural-burns-help

Potter, K.M., Escanferla, M.E., Jetton, R.M., Man, G., and Crane, B.S. 2019. Prioritizing the conservation needs of US tree spp: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats. Global Ecology and Conservation, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/

Scott, T. and K. Turner. 2014. Evaluating Rapid Response to a Goldspotted Oak Borer Diaspora. USDA FS General Technical Report PSW-GTR-251. Proceedings of the 7th California Oak Symposium: Managing Oak Woodlands in a Dynamic World.

USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest State & Private Forestry R5-RP-022 Oct 28, 2008

Zeleznik, Joe. 2008. Economic impact of emerald ash borer on North Dakota communities. CityScan 2008